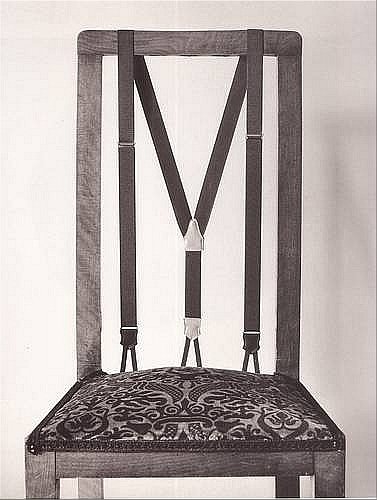

Hidden in a darkened, musty back room of a small furniture shop that exists along one of Venice’s labyrinthine passages, is an old chair. Long forgotten, entirely unremarkable, and barely recognizable as a piece of furniture, this simple wooden chair appears to the untrained eye as nothing more than junk.

Scraps of brittle leather along with frayed and faded silk cling to the back frame, held in place only by small, rusted tacks. The seat remains intact, but the nearly three centuries of dust and neglect has rendered the fine brocade fabric nothing more than a filthy, grey shadow of what it once was. The only clue to the historical significance of the chair are the little leather straps, still, after all these years, gripping firmly to the base of the seat at the exact spot the back frame of the chair connects.

This is the fate of the first suspender chair, once revered by nobility and the wealthy, now fallen so completely out of favor that no tangible record of the chair remains. No record, that is, with the exception of this forgotten, discarded Venetian chair.

The suspender chair was designed and built in 1717 by a self-taught woodworker and carpenter named Albertius Turstigno, a Venetian-born Dutch man (who, by most accounts, was actually a woman named Alberia). Albertius had built the chair out of a recent delivery of New World pine, but lacked enough wood to finish the back slats. Out of necessity, the long-lost legend contends, Albertius ran across the narrow street to a small dress shop and frantically searched for something that could support the back frame. He spotted two crossed straps of cow leather and fine royal blue silk, resting delicately on a mannequin.

The leather straps and silk accent fabric, intended as supports for a young, middle-class merchant’s daughter’s gown, were precisely what Albertius was seeking. Back in his workshop, Albertius secured the straps exactly as he had first seen them on the mannequin, a small “x” shape towards one end, reinforced and decorated by the blue silk.

For a moment, Albertius paused, then placed the straps over his shoulders with the small “x” resting near his lower back. Perhaps he had a vision of what these straps of leather and silk would one day become, perhaps he was merely planning out how to attach the straps to the chair frame. Perhaps it was just a moment of rest. No matter what, Albertius gently pulled the straps from his torso and went to work attaching them to the chair.

Albertius, by that time in 1717, had achieved some local renown for his innovative designs and use of rare materials imported from the New World. It’s said that the suspender chair took three months to sell, but once the first chair had been sold to the head of Venice’s most prosperous bank, demand for Albertius’s creation took off.

By 1732, financial and apprentice records from the shop indicate that Albertius had hired 20 new employees – 18 of whom were exclusively dedicated to building the suspender chairs. Albertius had also involved the dress shop in his production, including the owner’s family on the payroll as well.

However, by 1768, all mentions of the suspender chair and Albertius’s shop had disappeared from record, and the chair had become a forgotten relic of history. Speculation on the reason for the chair’s swift decline and disappearance indicates the toll of wars and power struggles with the Turks, Austrians, and French decimated the once powerful Republic of Venice. In 1797, the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed by Napoleon and Austria, created a new border for the ancient republic. Local Venetian politicians felt betrayed, and refused to recognize the new borders. The decline was nearly complete.

It would be a quarter of a century after the treaty before Albertius Turstigno’s invention would resurface, however, absent the chair that had necessitated its creation. History tells us that a man named Albert Thurston invented the modern suspender in 1822. Due to the fashionable high-waisted pants style at the time, the suspender took off, becoming the most popular article of men’s clothing until the uniforms of World War I accustomed men to wearing belts instead of suspenders.

It is unknown if Albert Thurston, inventor of the modern suspender, was related to Albertius (probably Alberia) Turstigno, but imagination suggests they were. It would, at least, be a more fitting tribute to this once-great chair now abandoned to obscurity.

Today, a few steps away from the lonely, old Venetian furniture shop is a street sign, rare in this city’s tangled avenues and maze of canals. Made of painted terracotta tiles, the street sign is secured with ancient plaster to the wall, as are most of Venice’s few street markers. Etched in the tile beneath the numbers, still faintly visible, but requiring close inspection, is a small inscription. It reads,

“a. Turstgno. 1717.”